I’ve just read Devin Fore’s remarkable and sometimes terrifying Soviet Factography: Reality Without Realism. Fore’s indifference to ascendant strains in Soviet historiography is magisterial: no attempt here to recuperate Socialist Realism, which remains an unmitigatedly bad object; no decolonial verbiage; nothing, blessedly, on the USSR as expression of eternal Russian imperialism. The book is rather, I’m tempted to say, almost militantly loyal both to October’s critique of centered subjectivity as well as to the hard anti-humanist sensibility of first-wave German media theory (without Kittler actually showing up much in the citations). If his previous work Realism After Modernism: The Rehumanization of Art and Literature shows how reification left its mark on the figurative arts of the Neue Sachlichkeit and related phenomena in capitalist Germany, its sequel turns to a deployment of reification against representation and humanism alike in the context of socialist construction. Apart from its theoretical interest, Soviet Factography is valuable simply for giving Anglophones huge amounts of new information. This is in the spirit of its object, though Fore doesn’t make much of the performative contradiction of writing a linear four-chapters-plus-intro-and-conclusion monograph about a movement that hated nothing so much as the traditional book. A box of index cards might have been more appropriate.

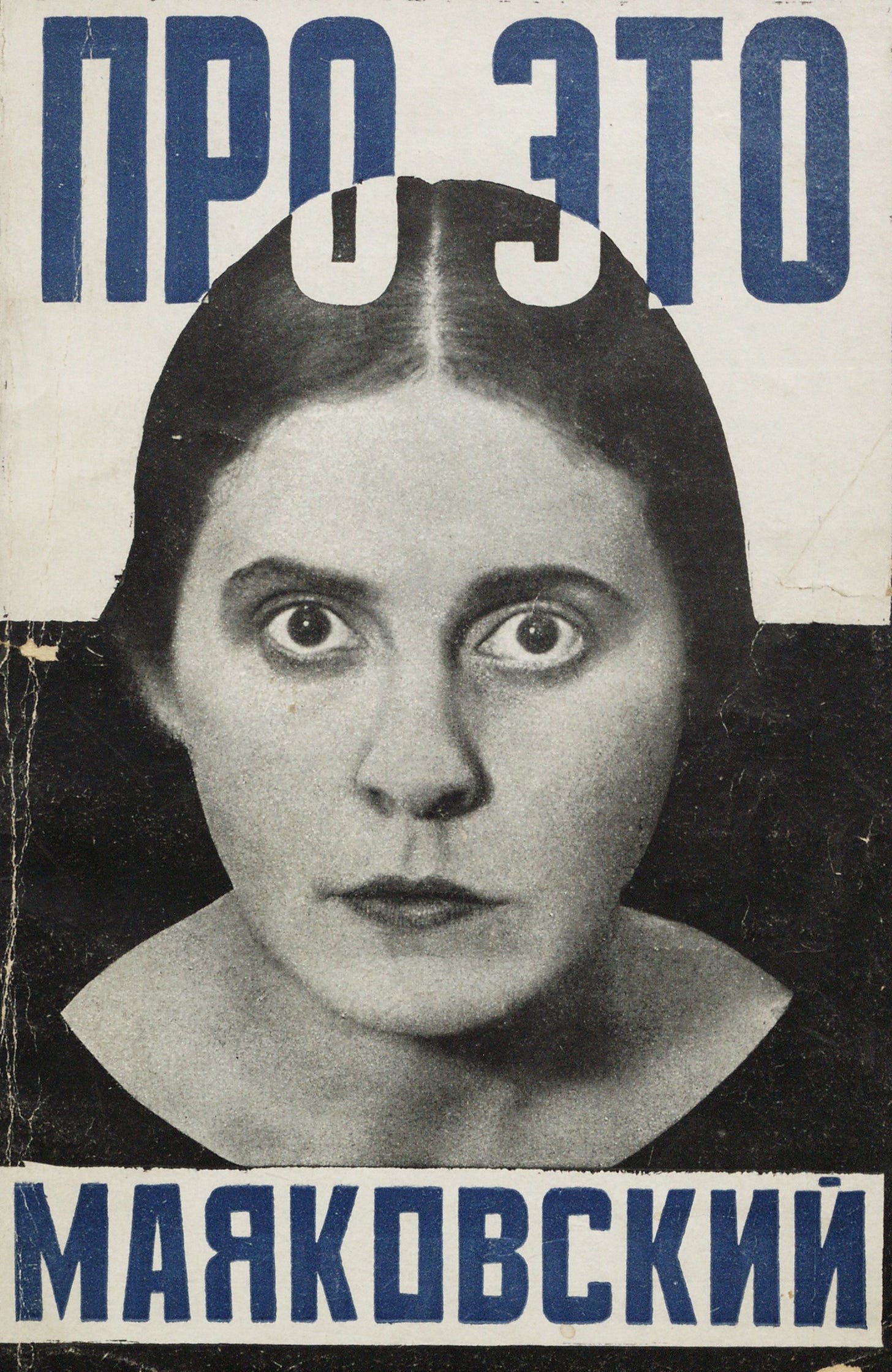

Factography could name a lot of things in the Soviet Union during the later 1920s and early ’30s. It was primarily a literary mode associated with the form of the ocherk (sketch or brief report). Fore nonetheless rightly insists that factographic prose must “be read with its subtending photographic conditions in mind.” Rosalind Krauss made the same point about Surrealism long ago, and indeed these apparently opposed currents turn out to have more to do with each other than might seem, insofar as both reject a correspondence theory of truth in favor of something more convulsive. Georges Bataille even turns up at the end of the book as an appreciator of Dziga Vertov’s informe. Photography and film, as Sergei Tret’iakov and his comrades in Lef / Novyi Lef took them up, had little to do with documentary realism in any subsequently familiar sense. They were, rather, like the “fact” to which they were assimilated, punctual, anti-totalizing, and anti-representational data, equivalent to a reading of the temperature on a given day, for example, or, more provocatively, to the hybrid prodigies and monsters (monstrare = to show) to which the word “fact” originally pertained in the early modern period.1 “Signs now began to converge with the objects that they designated” (this is Fore’s paraphrase of something that Andrei Platonov said). Factography sought “to align the time of events with the time of their inscription, and through this convergence, to achieve a condition of presence that abrogates representation as such.”

This is to say that factography is writing that hopes to annul writing. It hoped to annul consciousness, too. This poses a problem that seems to have manifested itself for readers most noticeably in boredom and fatigue. Factographic writing is tendentially “deverbative.” It heaps up substantives with few clues as to how they hang together. It’s impervious to hermeneutics. It also isn’t very much fun. Ideally, I suspect, the factographic ocherk would not have been read at all, since reading immediately produces delay and a split between the object and its inscription, between perception and thought. The ocherk therefore is (ideally) a kind of excretion or excrement expelled from the writer in his encounter with the fact: more somatic shudder—a mimetic, precognitive response to something—than act of communication. In this sense it recalls the seemingly distant paradigm of Aby Warburg’s pathos formula, partly because both share a filiation in late nineteenth-century German psychophysics: Robert Vischer in Warburg’s case, Ernst Mach for the factographers. The ocherk stakes the limits of logos. But as Derrida would suggest, expulsion of that which escapes the circle of spirit’s return to itself buttresses logos by constituting its proper supplement, its parergon. If so, then the relation of this anti-cognitive rationalism to the reified projective rationality of the socialist plan is perhaps more dialectically ironic than Fore suggests. We will have to deal with Hegel a bit.

Why? Because we need to get a bead on the Now and the This. Factography was a question of time and ostension. Symbolic cognition is mnemotechny; it responds to or maybe generates the temporal problem of anticipation and recollection (concepts, as Hans Blumenberg said, are traps). The factographers wanted to fit everything into the moment of inscription. This set them against the possibility of a transcendental subject, since the transcendental is a residue of the trace. Otherwise, there wouldn’t be a manifold to synthesize but just a sequence of isolated facts intuited by a correspondingly schizophrenic perceptual apparatus. It has always been a little unclear to me why the October crew were so viscerally opposed to transcendental subjectivity; wandering about as a pure receptor doesn’t sound particularly great to me. But that was what the factographers wanted, and Fore shows just how far they went to get there.

So, reflexology replaces reflection. There are sinister aspects to this. Tret’iakov et al. were closely allied with the League of Time, a group pledged to the “socialization” of temporality. The problem was that there were too many kinds of time in the early Soviet Union: the time of the factory, the time of peasant agriculture, the time of revolution, the time of the clock. The League wanted to synchronize all time to the latter. Temporal synchronization went hand in hand with the construction of a new public sphere by means of the clocklike regularity of the mass press, especially the daily newspaper, which was something of a fetish for nearly everyone in the 1920s. Fore’s (excellent) recent article on Soviet “proletarian feedback” shows how this model constitutes an alternative to Benedict Anderson and Habermas on the public sphere. Not to say that this proletarian public sphere (to invoke Negt and Kluge, two of Fore’s other bailiwicks) had nothing to do with its bourgeois counterpart; indeed, in certain respects its functions were strikingly similar, especially when it came to productivity imperatives. If everything could be measured, nothing could escape the immanence of synchronization, which in turn meant that nothing could be held up by the superfluous lag that we call cognition.2 Efficiency became its own telos. Tret’iakov took the idea to self-parodic extremes, as in the “kiss factory” passage from his ocherk collection Moscow—Beijing:

Kiss each other at this time. In 6 minutes it will be too late.

In one minute it is possible to manufacture 12 acts of kissing, each composed of 5 smacks on the lips apiece.

In the case of a larger assembly of participants (more than a company), it is possible to organize mass production of up to 60 kisses per minute.

Kiss each other in perfect time.

Of course, nobody needs to make kissing more efficient. But that’s as good an index as any of the paradox of Soviet rationalization. Socialist synchronization occurred in the absence of a most powerful mechanism, the market’s ratification of abstract labor time.3 Factography shows the extremes to which the disciplining of perception, cognition, and reaction had to go in the absence of the automatized corporeal-cognitive discipline of the value form. This was modernization by act of will. Given that the Soviet Union set production goals in accordance with planning rather than market signals, there was, strictly speaking, no difference between “rational” and “irrational” allocation. Had it really been collectively decided that kissing needed to be made more efficient, this would have been no more or less of a rational social determination than that iron production must rise 15%. In the context of rapid catch-up industrialization after the Civil War and the revocation of the New Economic Policy in 1928, the predictable consequence was that productivity standards for everything rose at once. Without naturalized wage compulsion and commodity exchange, it also became functionally impossible—except, ironically, by means of collective reflection—to distinguish sectors in which rationalization was rational and sectors in which it wasn’t.4 That is, general factographic acceleration under the sign of anti-cognitivism (elimination of the gap between sign and thing, between perception and reaction) would have been inconceivable without planning as its paradigm.

This contradictory structure of planned planlessness has its analogy in factography’s structure of inscription. Analogy is not quite the right word, though: rather, I think, the factographic mode of writing and the proto-Stakhanovite nexus of planning and heroic (irrational) exertion are more or less the same thing. The question turns on the movement from immediacy through mediation. Let’s return to Hegel, as promised. After its famous preface, the Phenomenology properly gets underway with a chapter on sense-certainty, sinnliche Gewissheit. Things appear to us initially exactly as they are, and this knowledge “immediately appears as the richest kind of knowledge,” as well as the truest (§ 91). (Marx similarly starts Capital with the observation that “The wealth of societies dominated by the capitalist mode of production appears in the form of an ‘enormous accumulation of commodities,’” as it reads in the new translation by Paul Reitter). But instantly, this turns out to be wrong: “this very certainty proves itself to be the most abstract and poorest truth. All that it says about what it knows is just that it is; and its truth contains nothing but the sheer being of the thing.” The whole of the critique of factography is already contained in this simple observation. Where things get interesting is in the following paragraphs, starting with number 92. Sense-certainty not only instantly refutes its own claim to fullness, but also, and more importantly, divides, iterates:

An actual sense-certainty is not merely this pure immediacy, but an instance of it. Among the countless differences cropping up here we find in every case that the crucial one is that, in sense-certainty, pure being at once splits up into what we have called the two ‘Thises’, one ‘This’ as ‘I’, and the other ‘This’ as object. When we reflect on this difference, we find that neither one nor the other is only immediately present in sense-certainty, but each is at the same time mediated: I have this certainty through something else, viz. the thing; and it, similarly, is in sense-certainty through something else, viz. through the ‘I’.

Consciousness thus starts with a subject/object split that privileges the latter as “simple, immediate being.” I don’t want to move too fast through what is after all a somewhat complicated book, but it’s important to know (spoiler alert) that the whole trajectory of the Phenomenology leads to a sublation of this immediately produced mediacy and all its subsequence convolutions in Absolute Knowing, the inwardizing recollection of the external forms of Spirit.

The factographic moment proper, however, arrives in § 95, with the intervention of writing. What is the ‘This’? ‘This’ appears in time and space as ‘Now’ and ‘Here’. (Time and space will eventually themselves turn out to be markers of Spirit’s self-movement rather than Kant’s pure forms of intuitions, but that is getting ahead of ourselves.) How to fix a ‘Now’ or a ‘Here’? With inscription:

To the question ‘What is Now?’, let us answer, e.g. ‘Now is Night.’ In order to test the truth of this sense-certainty a simple experiment will suffice. We write down this truth; a truth cannot lose anything by being written down, any more than it can lose anything through our preserving it. If now, this noon, we look again at the written truth we shall have to say that is has become stale.

A Now instantly ceases to be a Now, even if we freeze it in writing. Hegel continues in § 96: “The Now that is Night is preserved, i.e. it is treated as what it professes to be, as something that is; but it proves itself to be, on the contrary, something that is not.” This is an odd thing: the written Now becomes something other than the Now while nonetheless remaining a “self-preserving Now”—it’s become a mediated Now, a universal Now in general rather than this now, this Night. Thus, the universal is the real content of sense-certainty, and the universal emerges as the transcendental residue of inscription, a mnemotechny. At the end of the book, after the long path of Spirit’s kenosis, night returns: “Thus absorbed in itself, [Spirit] is sunk in the night of its self-consciousness; but in that night its vanished outer existence is preserved, and this transformed existence—the former one, but now reborn of the Spirit’s knowledge—is the new existence, a new world and a new shape of Spirit.”

Fore emphasizes at various points that the Now and This of factography are a darkness: absence of cognition, a black box. But factography’s Now and This are also immediately writing, which means that they’re immediately not themselves but rather mediated and universal. Technologies of inscription might be categorized effectively by their approach towards an absence of dynamic feedback mechanisms, as Mal Ahern has argued, of which the brain is the ultimate paradigm. A notepad requires relatively more brain-mediation than does a camera. The factographic critique of realism and abstraction alike was that, despite their apparent opposition, both representational modes left too many blanks for the mind: too much phenomenological density in the former, too little in the latter, but in either case an irksome discrepancy between perception and cognitive totalization. The ocherk was by contrast meant to leave no gaps for the brain to fill in. Feedbackless inscription putatively generates no lack in totality for which to compensate with ideological or simply reflective cognition, because the possibility of dialectical totalization is foreclosed in advance. That is, the cut of montage—the twentieth-century avant-garde’s formal device par excellence—was apotropaic (self-)castration meant to protect the real against ideological feedback and thus to facilitate not the representation but rather the construction of reality as an open-ended process. Yet the iterative spacing of even the most desubjectivized recording process ceaselessly rebuilds the transcendental, while leaving behind as its remnant the unsublimated materiality of the inscriptive technology as such. By skipping a mediating step between techne and perception, the entirety of the inscription is (again, supposedly) at once recuperated to the latter while technicity itself falls out of view, notwithstanding the marvelous self-reflexivity of factographic masterpieces such as Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera: if the camera is an eye, then the fact that it’s also a camera becomes rather an annoyance. In consequence, factography fell into an arms race against itself to develop ever-more immediate, ever-less cognitive media. This drive was analogous, as I’ve already said, to the logic of socialist production, which removes the feedback mechanism of market-based price signals without, however, simultaneously severing the link between individual labor contributions and access to the social store.5

I have to say that Fore does not entirely have the courage of his convictions. I don’t mean that the absence of any but the most fleeting references to Stalin (or to the fact that Tret’iakov died in prison in 1937) is politically evasive; I’m proposing no such critique, as I likewise resist the teleological urge to read subsequent failures of the Soviet Union in its avant-gardist DNA. But the obvious weakness of factography’s radical anti-cognitivism does force him into a meek caveat: “In sum, the techniques pioneered by Tret’iakov cannot simply be transposed into other contexts, for the efficacy of factographic work presumes specific geopolitical conditions and, equally, a specific historical conjuncture. Positivism may prove to be progressive at revolutionary moments, but it is instead reflection and critique that are needed in phases of political stagnation”—namely our own. This also leads to his astonishing suggestion that reality is “spontaneously legible” in revolutionary periods. I would suspect the opposite: that the fog of war is nowhere denser than in the chaos of immediate communist measures, which certainly present themselves as practical necessities but not as spontaneous symbolic forms. All the same, modesty is good council here. We are not in position to say that we know better than the early Soviets. Nobody has come closer to communism than they did, whereas our ideas are speculative. Still, very different inscriptions of temporality have come down to us from the same world: Platonov’s, for example.

During Italy’s “Creeping May” of the 1970s, the artist and Lotta Continua militant Pablo Echaurren was to devise an iconography of mostricciatoli, or little monsters: avatars of the mutations of revolutionary subjectivity. Jacopo Galimberti has written a nice little book on the topic.

I’ll avoid saying anything about the more recent vogue for queer temporalities.

David Joselit has developed an interesting reading of the socially synthetic functions of the commodity form and political propaganda in capitalist and socialist contexts, respectively, the endpoint of which is their “synchronization” in the globalized art world. Although a bit schematic, I find this hugely useful, among other things as an art historical update on Debord’s distinction between the diffuse and concentrated spectacle.

I recommend this piece by Jasper Bernes for its analysis of some schemes to overcome the value form, particularly the Fundamental Principles of Communist Production and Distribution produced by the GIK (Gruppe Internationaler Kommunisten, a German-Dutch Councilist group) in 1930.

Jasper Bernes is again good on this. See also his article “Planning and Anarchy.”

Give your whole being to the state. Make your body a part of the collective machine. Be useful! Teach by example. Take the shell of the capitalist package to imbue new meaning into the products you consume. And bring art into everday life (byt).