-graphy and -logy revisited

Yet further considerations on Panofsky and friends

I’d like to elaborate on thoughts about the conceptuality at stake in iconology that I proposed in my last missive. The topic is probably of interest only to a sliver of the people who subscribe to this newsletter, though perhaps to a few more of those who actually read it. A few days ago, I happened to be perusing Andreas Malm’s The Progress of This Storm: Nature and Society in a Warming World, a book that makes basically correct points but in such an unpleasantly dick-swinging way that they seem wrong. One of his basically correct points is that, contrary to New Materialists, Bruno Latour, and so on, any coherent definition of the term “agent” implies intentionality, which in turn implies having a mind. What differentiates agential status from consciousness as such is, furthermore, planning. As Malm puts it, on pages 85-86, “the mind of the agent assumes a specific mode of intentionality—not any kind of mental directedness towards an object, such as when I think of the dead bird I saw in the forest, but a peculiar aiming at an X that has not yet come about. I intend to wake my child, who is not in this moment awake; I intend to end my life, which has so far not ended.” (One wonders how Malm comes up with these examples.)

This seems reasonable. Nonetheless it may be an impoverished account of what intentionality is. Imagine a sprinter waiting for the start of a race. She knows that when the starting pistol fires, she will run. But is that knowledge a project (an Entwurf) that she conceives and then executes? Or is the stimulus/response action rather the event to which the intention relates as an account, whether ex ante or ex post facto? That is, are “intentions” sometimes explanations or even just mnemonics rather than plans? Or, with Nietzsche: when lightning flashes, which is the doer and which is the deed?

Now consider Erwin Panofsky’s excursus on the (still rather fuzzy) difference between “iconography” and “iconology” in Meaning in the Visual Arts (the brackets are in the original):

[The suffix “graphy” derives from the Greek verb graphein, “to write”; it implies a purely descriptive, often even statistical, method of procedure. Iconography is, therefore, a description and classification of images much as ethnography is a description and classification of human races: it is a limited and, as it were, ancillary study which informs us as to when and where specific themes were visualized by which specific motifs. It tells us when and where the crucified Christ was draped with a loincloth or clad in a long garment; when and where He was fastened to the Cross with four nails or with three; how the Virtues and Vices were represented in different centuries and environments. In doing all this, iconography is an invaluable help for the establishment of dates, provenance and, occasionally, authenticity; and it furnishes the necessary basis for all further interpretation. It does not, however, attempt to work out this interpretation for itself. It collects and classifies the evidence but does not consider itself obliged or entitled to investigate the genesis and significance of this evidence: the interplay between the various “types”; the influence of theological, philosophical or political ideas; the purposes and inclinations of individual artists and patrons; the correlation between intelligible concepts and the visible form which they assume in each specific case. In short, iconography considers only a part of all those elements which enter into the intrinsic content of a work of art and must be made explicit if the perception of this content is to become articulate and commensurable.

[It is because of these severe restrictions which common usage, especially in this country, places upon the term “iconography” that I propose to revive the good old word “iconology” whenever iconography is taken out of its isolation and integrated with whichever other method, historical, psychological or critical, we may attempt to use in solving the riddle of the sphinx. For as the suffix “graphy” denotes something descriptive, so does the suffix “logy”—derived from logos, which means “thought” or “reason”—denote something interpretative. “Ethnology,” for instance, is defined as a “science of human races” by the same Oxford Dictionary that defines “ethnography” as a “description of human races,” and Webster explicitly warns against a confusion of the two terms inasmuch as “ethnography is properly restricted to the purely descriptive treatment of peoples and races while ethnology denotes their comparative study.” So I conceive of iconology as an iconography turned interpretative and thus becoming an integral part of the study of art instead of being confined to the role of a preliminary statistical survey. There is, however, admittedly some danger that iconology will behave, not like ethnology as opposed to ethnography, but like astrology as opposed to astrography.]

Of these two famous paragraphs, inserted as they are as a veritable parergon within this manifesto’s unbracketed text, the obvious thing to mention is that nobody has ever managed to keep iconography and iconology straight. Or maybe it would be more accurate to say that no art historian has ever thought of herself, in these terms, as an iconographer rather than an iconologist. It’s interpretation all the way down. Nonetheless art history if not the human sciences in general seem unable to resist slicing the pie between lowly bean-counting and properly hermeneutic activity. Hans Sedlmayr’s distinction between “first” and “second” art history is exactly the same in essence and only a little more mystical in practice.

Let’s go back to the Greek, though. Graphein, to write, “implies a purely descriptive, often even statistical, method of procedure.” But why? Because graphḗ is a technical supplement, a dead tool, whereas logos is the living word. I’ve already alluded to Derrida and it would not be hard to demonstrate how Panofsky’s edifice is logocentric and invites deconstruction. I’ll forgo the demonstration while proceeding in what I hope is a likeminded vein.

The inquiry turns again on the problem of immediacy that I highlighted in my last post. The “descriptive, even statistical” method of iconography is fundamentally technical. The discredit that attaches to it is that of the letter without the spirit. Iconology, too, is written, needless to say. But writing’s technicality and supplementarity is in this latter case subsumed to the “intrinsic content” or “correlation between intelligible concepts and the visible form” that we find in a symbol (or “symbolic form”) properly construed. Where does iconography belong, then? Clearly to the middle of the three levels of interpretation, that of “iconographical analysis” as opposed to either “pre-iconographical description” or “iconological interpretation.”

Here is where Panofsky’s analogies get strange. For whatever reason, it strikes him that the best way of explaining things is to say that ethnography is to ethnology as iconography is to iconology. And what is ethnography? “A description and classification of human races.” Why is this something we would want to exist at all?—or to put it more generously, what are ethnography’s conditions of possibility? Presumably, the existence of “human races” to start with, as ethnography’s data. Which is to say that Panofsky has, curiously, again relied on just the same “everyday” fact that he offers in Renaissance and Renascences (as I’ve described before): “That the skin of a negro is dark throughout is a matter of common, everyday experience; but who is to judge of the ‘harmonious’ relation between, say, the length of a foot, the width of the chest and the thickness of the wrist without combining empirical observation with archaeological research and exact mathematics?”

Ethnography as Panofsky seems to understand it would then be nothing other than the “exact” (technical, numeric, formalized) ordering of the immediate fact of blackness, or of any other racial given (though blackness is clearly paradigmatic as far as he is concerned). As I hope to have shown in my last outing, however, the immediacy of race itself is mediated, was itself an outcome of the technical procedures (measuring, quantifying) that reappear, in Panofsky’s “ethnography” and “iconography,” as pre- or at best quasi-conceptual graphein on the threshold to properly hermeneutic logos. This production of race was homologous to and perhaps deeply implicated in the autonomization of the aesthetic in modernity—a process to which iconology’s notorious insistence on “meaning” has always seemed to bear a confounding relationship. Hence much ink spilled over the missed encounter between modernism and the dominant strand in twentieth-century art history.

But let’s return to that on some other occasion. Relying on Oxford verbatim, Panofsky furthermore (and astonishingly) proposes that ethnography is a “description of human races,” ethnology a “science of human races,” as, by implication, iconography is Bildbeschreibung whereas iconology is Bildwissenschaft. What is a science? Not mere inscription. A science involves “thought” or “reason”: logos. Any -logy is an account of reasons. A science is an account of the “genesis and significance” of given (self-)evidence, which however in the case of art objects, at least, always already splits into perceptual immediacy and “secondary or conventional” traits that require at least some form of graphein to be registered, as for instance in Panofsky’s well-known observation that Leonardo’s Last Supper would just look like a dinner party to someone unfamiliar with Christian myth.

A full analogy to Panofsky’s three-tiered structure of iconology would therefore look like this: 1. the pre-iconographic fact of blackness, or of skin being “black throughout”; 2. the “description and classification of human races” as data akin to iconographic motifs (as we have seen, in historical reality this stage crucially precedes and grounds the immediate “fact” in stage one); 3. the “comparative” science of race, which must make “explicit” the “intrinsic content” of human difference—at least, “if the perception of this content is to become articulate and commensurable.”

The last two qualifiers strike me as important. Graphḗ is not yet discursive, and although it consists in measurement, neither is it yet a practice of commensurability, of the articulation of difference in an economy of reasons (what Panofsky calls “science”) and therefore the launching of difference into a certain exchangeability within the immanence of a culture. “Culture” we could in turn describe quite classically as an articulated totality of meanings. This is the terrain of German hermeneutics from Dilthey to Gadamer; Panofsky distinguishes himself within the tail end of the tradition mostly for his loyalty to Cassirerian “symbolic form” as opposed to plumbing the less formalized phenomenological background or Lebenswelt. By the same measure, though—and likely in spite of himself—I hope to have indicated by now that Panofsky’s model of iconology is also in its way a -logy or account of the production of the non-conceptual thanks to the violent incision of graphḗ: the technical supplement that at once excludes both (aesthetic, perceptual) immediacy as well as the “intrinsic” logos, or properly interpreted symbolic form. Or to put it differently, the -graphy in iconography is not merely a step on the ladder to the -logy in iconology but is rather the preliminary inscription that makes the immanence of the symbol plausible at all.

At this point, though, we can circle back the way I posed the question of intentions in the context of Malm’s self-proclaimed anthropocentrism (which I would submit still has much to do with the post-Renaissance “anthropocracy” to which Panofsky alludes at the end of Perspective as Symbolic Form). Let’s do this by reminding ourselves of Blumenberg’s contention that concepts are much like traps—or more radically, that a trap is a concept in material form. A sprinter waits for a starting gun. Her intention of running when it shoots is not a concept as we usually understand concepts; it possibly isn’t even an intention in the way Malm is talking about them. But it does translate a stimulus—a “secondary or conventional” signifier that has its specific meaning only within the semiotic realm called “track sports”—into bodily action. The runner’s automatized response lies in wait for its signal as a trap waits for its prey.

In that case, why not call this sort of “intention” a “concept” in Blumenberg’s terms? Well, obviously, because there is very little that’s discursive about it, little that’s “articulate and commensurable”; there’s little of the logos in the -logy involved here. Any account of reasons that the sprinter might give herself, or others, for her lightning-like burst into action (Nietzsche again) will be either premature or belated. Any such science will be one of traces.

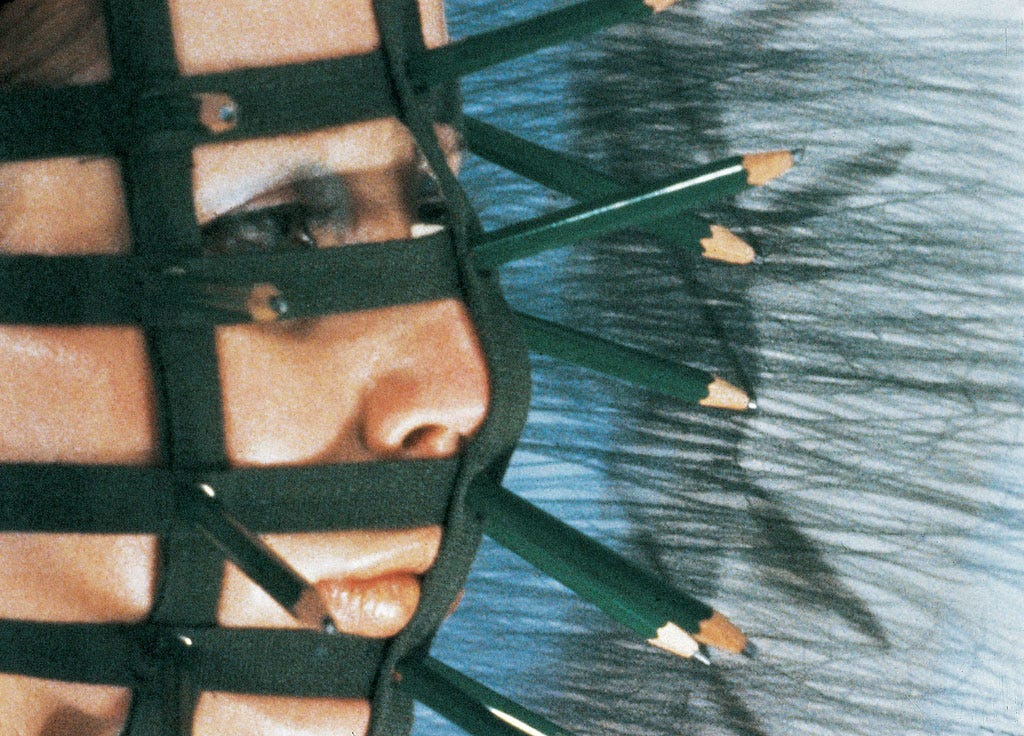

I’d like to suggest, finally—and this is surely enough for today!—that the sprinter’s reflex is accordingly the inverse of Warburg’s Pathosformel. The conventional “iconographic” sign of the starting pistol’s shot instantly translates itself into somatic excitation. What happens in the Pathosformel? A somatic/affective charge translates itself into a sign through the threshold of non-conceptual formalization. In either case, the account or -logy that relates to the event is inherently anachronic. It comes before or after what it explains, or purports to explain. In this sense, the “French Warburg” of Georges Didi-Huberman et al. is not so off the mark: iconology as Panofsky codifies it is the long shadow of Warburg’s inassimilable untimeliness. But if we also take seriously Danny Marcus’s suggestion that the Middle Passage can be understood as a “horrific Pathosformel”—which is what I’ve been trying to do in this post and the last one—then it does not seem far-fetched to hypothesize that the modes of interpretation that fall on either side of pre- or proto-conceptual iconographic inscription, namely perception of the “immediate” aesthetic fact and interpretation of the “intrinsic content” of a symbolic form, depend on a dismembering graphḗ (or “horrific Pathosformel,” now generalized as the structure of the trace) as something more than “a purely descriptive, often even statistical, method of procedure.” What to make of Panofsky’s quip that iconology might behave “not like ethnology as opposed to ethnography, but like astrology as opposed to astrography” is a question I’ll leave for another day.