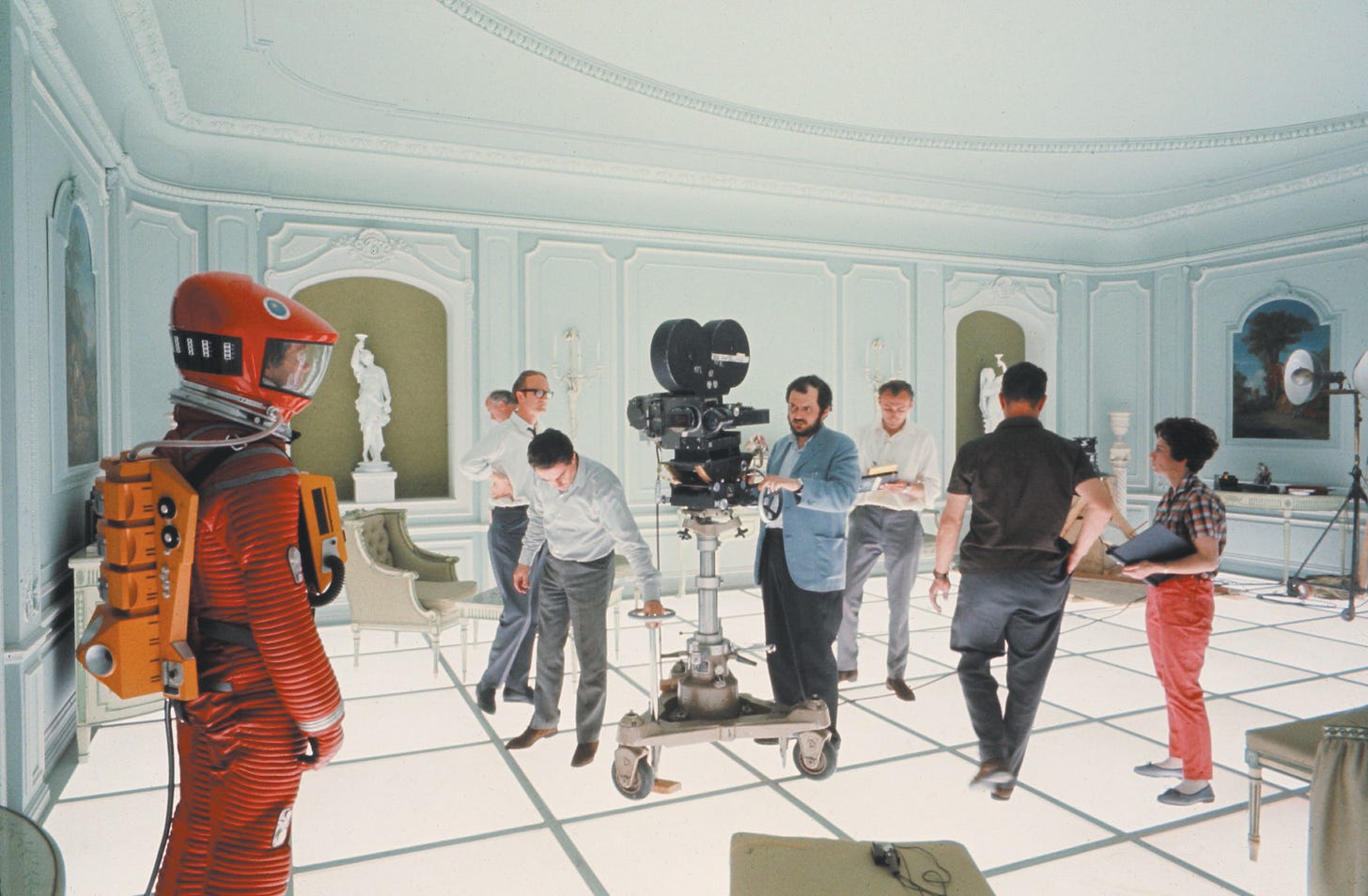

I went to a screening of 2001: A Space Odyssey and then, as one does, went back and read the late Annette Michelson’s touchingly overblown article on it, “Bodies in Space,” which was published in the late magazine Artforum in 1969. In the hangover of AI euphoria, the most striking thing about Michelson’s interpretation is how little she cares about HAL. Having seen the movie nine times, what matters to her instead is 2001’s place in the great arc of human evolution, which is why she drops a truckload of legitimating and typically mid-century names: “Like Fénéon’s descriptive criticism of painting, like Mallarmé’s assertion, to Degas, that ‘poetry is made with words rather than ideas,’ like Robbe-Grillet’s attack on Metaphor, Stravinsky’s rejection of musical ‘content’ or ‘subject,’ and Artaud’s indictment of theatrical text…”—and so on. What is this rapture for? Well, it does eventually come down to something more substantial. Because 2001 reduces cinematic “action” (Michelson repeatedly calls it an “action film”) to continuous movement and the viewer’s bodily and phenomenological engagement in same, rather than plot or character, the movie is a training ground for a new kind of embodied spectatorship, or “carnal knowledge.” As she puts it, scare-quoting nobody in particular: “The film’s ‘action’ is felt, and we are ‘where the action is.’ Its ‘meaning’ or ‘sense’ is sensed, and its content is the body’s perceptive awaking to itself.”

What do you do with an awakened body? You work. As Michelson sees it, Kubrick’s astronauts are almost constantly absorbed in various tasks. By extension, so is the audience. The film’s “total formalization” (shades here of Benjamin’s “blue flower in the land of technology”) serves a “maieutic” purpose, that of adjusting the viewer to the literally disoriented space of weightlessness. Zero gravity makes even the simplest tasks agonizingly as well as funnily difficult. In good modernist fashion, this doesn’t only alienate us from normal experience, but also makes us perceive normality in a new way. Abstraction makes the stone feel stony: “the voyage of the astronauts ultimately restores us, through the heightened and complex immediacy of this film, to the space in which we dwell.” Michelson’s paragraphs on this visceral yet estranged immediacy are more convincing than her world-historical fluff, which I think corresponds to the twenty-first-century’s experience of the movie itself. We tend to see (or at least I see) 2001 as an excellent deadpan comedy sandwiched between two weird bonus scenes, that is, the bit with apes and the bit with a lightshow. Michelson is good on funniness:

A Space Odyssey, then, proposes, in its epistemology, the illustration of a celebrated theory of Comedy. In a film whose terrain or scene of action is, as we have seen, the spectator, the spectator becomes the hero or butt of comedy. The laugh is on us; we trip on circumstance, recognizing, in a reflex of double-take, that circumstances have changed. Tending, in the moment which precedes this recognition, “to see that which is no longer visible,” assuming the role of absent-minded comic hero, “taken in,” we then adjust in incomprehension, “taking it in.” Kubrick does make Keatons of us all.

I would go further than this. 2001: A Space Odyssey is structured as a series of blackout gags. A sequence happens, and then there is a break with some black screen time, and then another more or less unrelated sequence happens. Some of the shtick has dated. Gender roles change far less than aeronautics in Kubrick’s future. As Michelson notes, though, most of the funniness comes from a classically Bergsonian confusion between the animate and the mechanical. “HAL, the computer as character, reverses the comic ‘embarrassment of the soul by the body’ in being a mere body embarrassed by the possession of a soul.” She has less to say about Keir Dullea’s wonderfully minimal Dave, whose hilariousness is that of extending the Kuleshov effect to the duration of an entire performance.

Something a bit off happens in Michelson’s analysis around this point, however. Comedy has the intermittent structure of the blackout. It “trips” us up in a double-take. (Near the end of the essay it becomes evident that she means to allude to the psychedelic notion of the “trip” as well.) But at the same time Michelson wants to argue that continuity is all in 2001. So, how does disruption relate to flow? Through the iterative rhythm of training. Or Beckett’s “Fail again. Fail better.” Or something like Chaplin’s interaction with the machine in Modern Times, which she doesn’t mention. Because, to remind you, we are in 1969, Michelson discusses all of this in terms of Piaget’s genetic epistemology, with each “process of equilibration ending in the creation of a new state of disequilibrium,” followed by more equilibration, and so on, until we successfully reach adulthood. In Kubrick’s “maieutic” film, “ontogeny repeats a philogeny.” But it does so at a higher, presumably Aquarian level, on the far side of bourgeois subjectivity: “To be ‘mature’ in our culture is to be ‘well-balanced,’ ‘centered,’ not easily ‘thrown off balance.’ Acceptance of imbalance is, however, the condition of receptivity to this film.” Hence its appeal to the Youth.

Do the youth luxuriate in their disorientation? No: they get down to getting things done. They adjust to new and ever-more pressing tasks. This seems not always to match what happens in the movie. There are good chunks of simple hanging-out time (laying around in underpants; playing chess with a computer), as one would expect on a spacecraft with not much to do on it. Michelson wants to rush past this dead time towards the no less excruciatingly extended moments in which Dave and his pal Frank methodically fix a circuit, operate a pod thing, or push buttons:

The manner in which all directed movement is endowed with the momentousness of the task indicates the reinvention of those coordinates for operational efficiency. Total absorption in their reinvention creates a form of motion of extraordinary unity, that of total concentration, the precondition of Style, a style we normally recognize as the quality of dance movement.

It isn’t just any Style or any dance at stake, though:

It would be interesting, then, to consider a style of movement created by the exact inversion of that negation of weight (its retrieval in fact), which animates the Dance of our Western historical tradition. More interesting, still, perhaps, is the realization that the style created by the astronauts in movement, in the reinvention of necessity, does indeed have a special affinity with that contemporary dance which proceeds from the radical questioning of balletic movement, the redefining and rehabilitation of the limits of habitual, operational movement as an esthetic or stylistic choice.

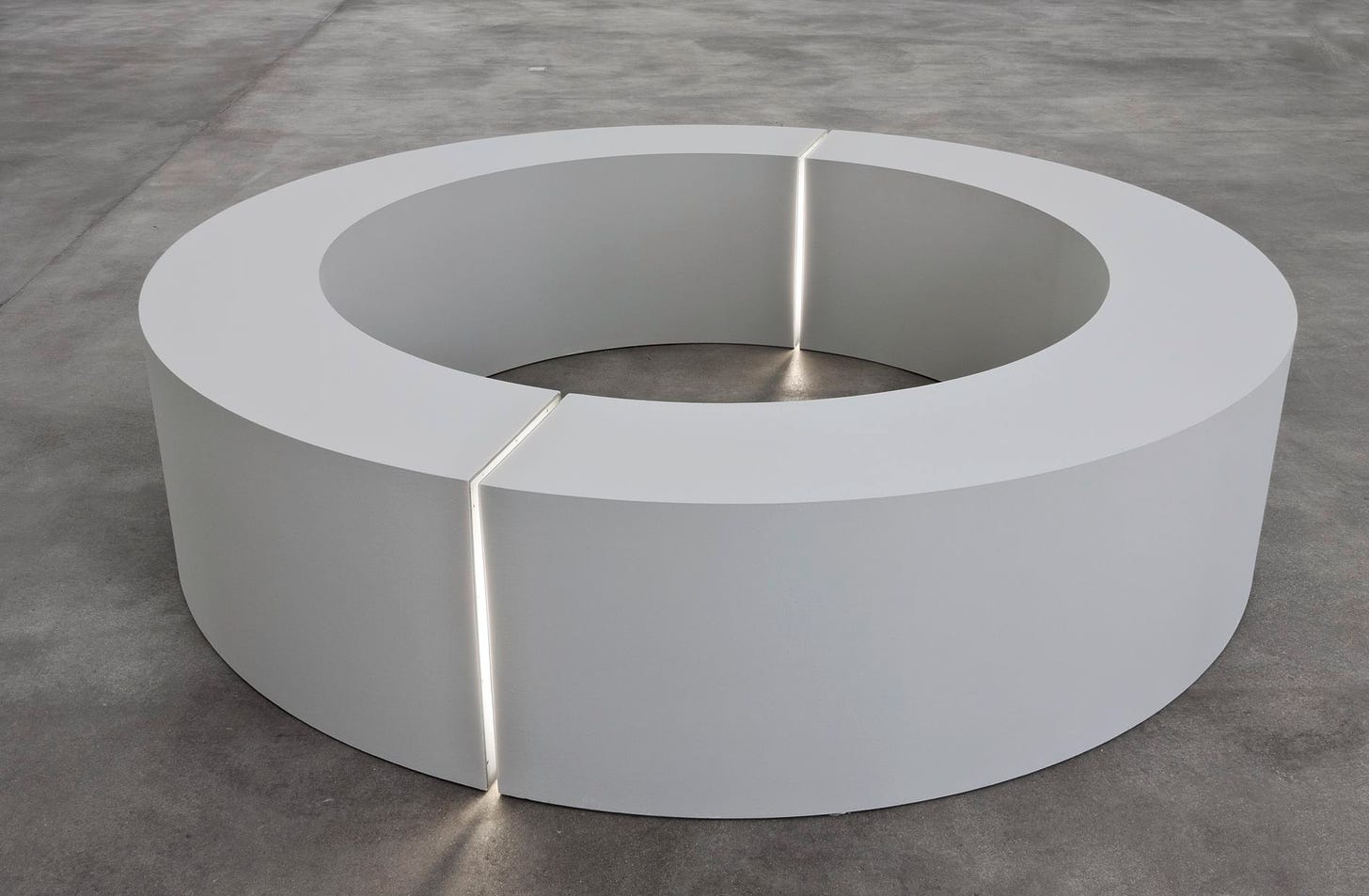

Michelson then mentions “Cunningham, Rainer, Whitman, Paxton,” thus making the connection explicit. The new Judson dance is “task performance,” “total absorption in operational movement… in the interests of functional efficiency.” To be an awakened body is to be good at doing things. It is also to accept imbalance. And it is to make instrumental practice an aesthetic principle in its own right, distinct from the now-repressed moments of listlessness that also characterize Dave and Frank’s pre-HAL crisis life on Discovery One. The endlessness of task-orientation is a Minimalist aesthetic in specific as well as generic senses. The great treadmill sequence near the beginning of the film’s second part epitomizes the Minimalist sensibility. In “Art and Objecthood,” from 1967 (also published in Artforum), Michael Fried describes Minimalist endlessness in a way that hasn’t been much improved. This is in relation to Tony Smith’s Die, a six-foot-square steel cube, and by extension to his famous anecdote about driving on the unfinished New Jersey Turnpike:

Like Judd’s Specific Objects and Morris’s gestalts or unitary forms, Smith’s cube is always of further interest; one never feels that one has come to the end of it; it is inexhaustible. It is inexhaustible, however, not because of any fullness—that is the inexhaustibility of art—but because there is nothing there to exhaust. It is endless the way a road might be, if it were circular, for example.

Similarly, Kubrick’s gravitational treadmill is circular and could go on forever. Or more pertinently, as long as the human body jogging on it can hold out. An astronaut’s work is never done. The strange thing is that Michelson sees this as utopian rather than nightmarish. The fact that “task” and “work” are very similar things doesn’t seem to occur to her; or if it does, it weirdly doesn’t bother her much.

I’ve slowly been leading up to the suggestion that “Bodies in Space” is a prehistory of what we now call precarity, the temporal signature of neoliberal labor. It’s striking that Michelson’s explicit recognition of the similarity between Piagetian sensory-motor training and efficiency-maximizing “task-performance” still comes down so decisively on the libertarian side: hope in the youth and their carnal knowledge. After Boltanski and Chiapello, it’s easy to diagnose such naïveté.

In a great article on Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity, the film scholar Mal Ahern shows where “workflow cinema” would end up forty-odd years later. To remind you, the movie consists mostly of long tracking shots—assisted with some fancy editing and near-constant CGI, of course—and it was released in 3D, which produces a kind of phenomenological immersion towards which Michelson seems to grasp (without, noticeably, ever referring to the by-then démodé 3D cinema of the 1950s; in this respect, it would be interesting to compare both 2001 and Gravity to Werner Herzog’s rather goofy 3D cave movie). Far more manically even than Dave trying to shut down HAL, Sandra Bullock’s body and mind are here at all moments tasked to the limit just to survive. As Ahern puts it: “More than any recent Hollywood film, Gravity presents the body as mere operational device, a cursor, an avatar who performs a set of actions.” Most of what we see is what Bullock sees, and since what she sees is an endless flow of video game-like problems to solve, there is little space for the classically psychoanalytic filmic apparatus of projection, suture, and so forth; “the immersive point-of-view shot doesn’t signal identification so much as an alliance between viewer, camera, and character.” Though constantly and fetishistically on view, Bullock’s body, and ours, accordingly recedes behind instrumental problem solving. “Her task, like ours, is simply to organize the overwhelming flow of visual data she receives through her visor. Her eyes and mind just happen to reside in a body”—much like those of a drone pilot, as Ahern points out. This is what a lot of work is like these days.

I should mention that I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey at Flix Brewhouse, a theater chain in which one is permitted, nay encouraged to order and consume beer, burgers, and so forth in exceedingly plush, physically isolating little pods. Cinema in the twentieth century got a lot of ideological mileage out of its mode of “simultaneous collective reception,” its odd way of uniting an audience in their separation. Flix Brewhouse enforces a very different bodily engagement with film, one modelled, instead, on the late bourgeois interior, or more specifically the man-cave. The premise of the experience seems to be that you can watch a movie exactly as you would at home, just on a bigger screen. (Silent if not always virtuosic servers bring out your order; ours fumbled a handful of plates in front of us about half an hour into the movie.) Consumption, then, converges with production in its orientation to task. My carnality was adequately fulfilled.